Pretrial Risk Assessment and SB 10

This past August, Governor Jerry Brown signed Senate Bill 10 (SB 10) into law. With SB 10, California became the first state to eliminate the use of cash bail in its criminal justice system. The elimination of cash bail is an important step to remedying the disproportionate adverse effects that pre-trial detention has on low-income defendants who are predominantly people of color.

Unfortunately, SB 10 replaces cash bail with a system that utilizes “risk assessment tools” in order to decide whether a defendant is incarcerated before their trial. While risk assessment tools possess the veneer of objectivity, they have the potential to worsen the same racial and class biases that SB 10 aimed to ameliorate.

Prior to SB 10, a person pleading not guilty to a crime would either be released conditional on payment of bail or incarcerated in jail until the trial. Thus, low-income defendants who could not afford to post bail would face three choices: go into debt in an effort to pay bail, stay in jail while waiting for the trial (sometimes for years), or plead guilty. With the elimination of cash bail, a new system was put in place to decide which defendants should be incarcerated before their trials (e.g. flight risks or those who may threaten public safety if released).

Under SB 10, judges and administrators in each jurisdiction will now use risk assessment tools of their choice to classify a defendant as having either a low, medium, or high risk of committing a crime or failing to attend court. Defendants classified as low risk will be released (which a judge can overrule), while those at high risk will be incarcerated. These risk assessment tools are machine learning algorithms.

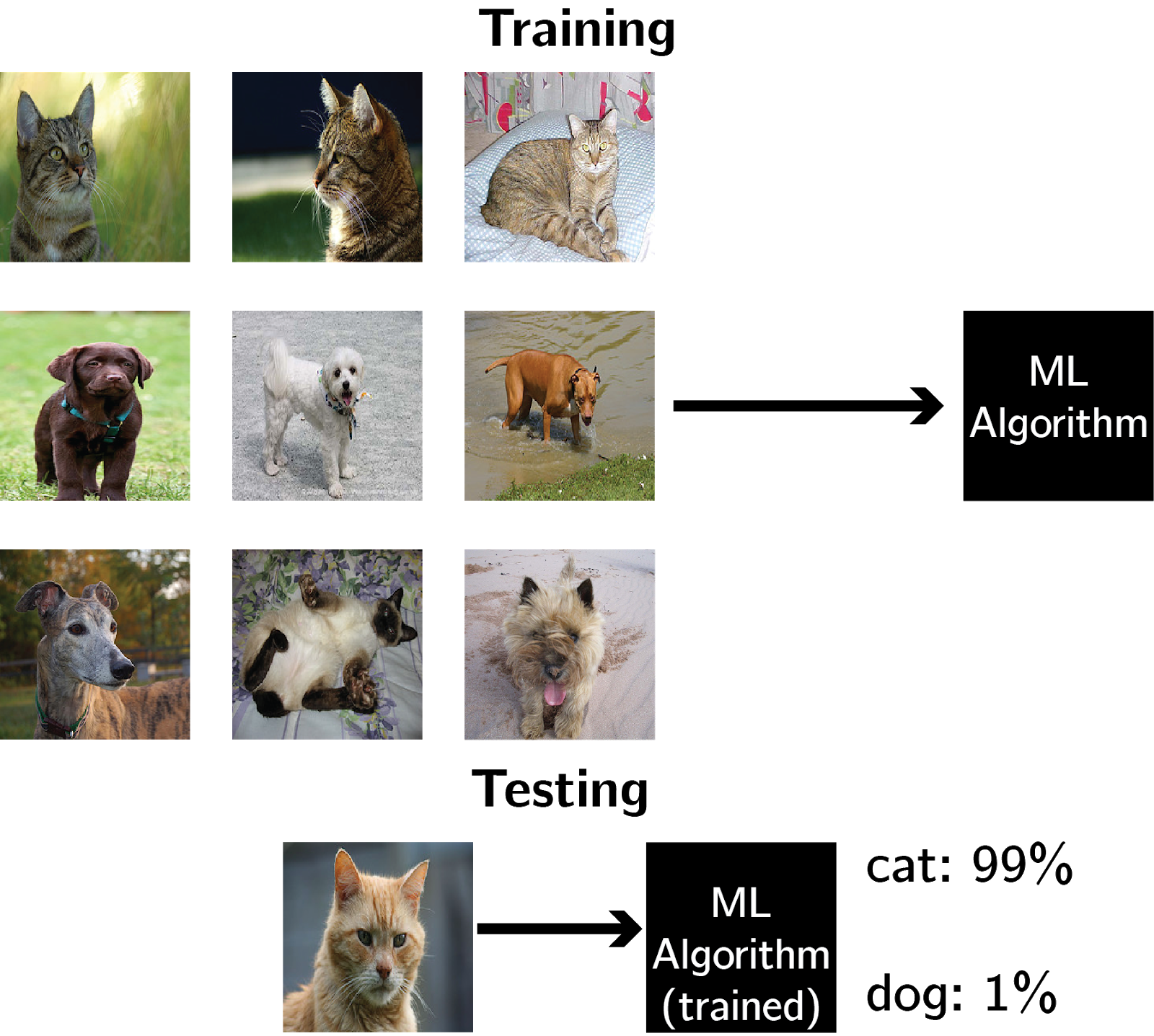

A machine learning algorithm completes a task without being explicitly programmed to do so by utilizing many examples of that task where the outcome is known. For example, consider the task of identifying an image as a cat or dog. A machine learning algorithm learns to classify by training on a large batch of cat and dog images with known labels. The algorithm examines each image’s features (in this case, the color and intensity values of the pixels) and outputs the probability that the image is a cat. If it was wrong (which, initially, it will be), the algorithm slowly corrects itself until it classifies the images correctly. Thus, it does not need to be explicitly programmed, only optimized by looking at labeled data.

Pretrial risk assessment operates similarly. Now, the task is to assess whether a person is likely to commit a crime or fail to attend a court hearing. The features, instead of pixel colors and intensity, are quantifiable aspects of the person and case: for example, the type of crime or the defendant’s criminal history. The risk assessment tools are trained on large datasets of past crimes, and thus are able to compare the current defendant’s profile to those that the algorithm trained on.

Here’s the problem: just because machine learning algorithms are mathematical in nature does not imply they are objective. A machine learning algorithm is beholden to the quality of the data on which it is trained. It is well known that, holding all other features constant, the criminal justice system disproportionately negatively affects people of color. Thus, these risk assessment tools are trained on biased datasets and therefore doomed to propagate these biases.

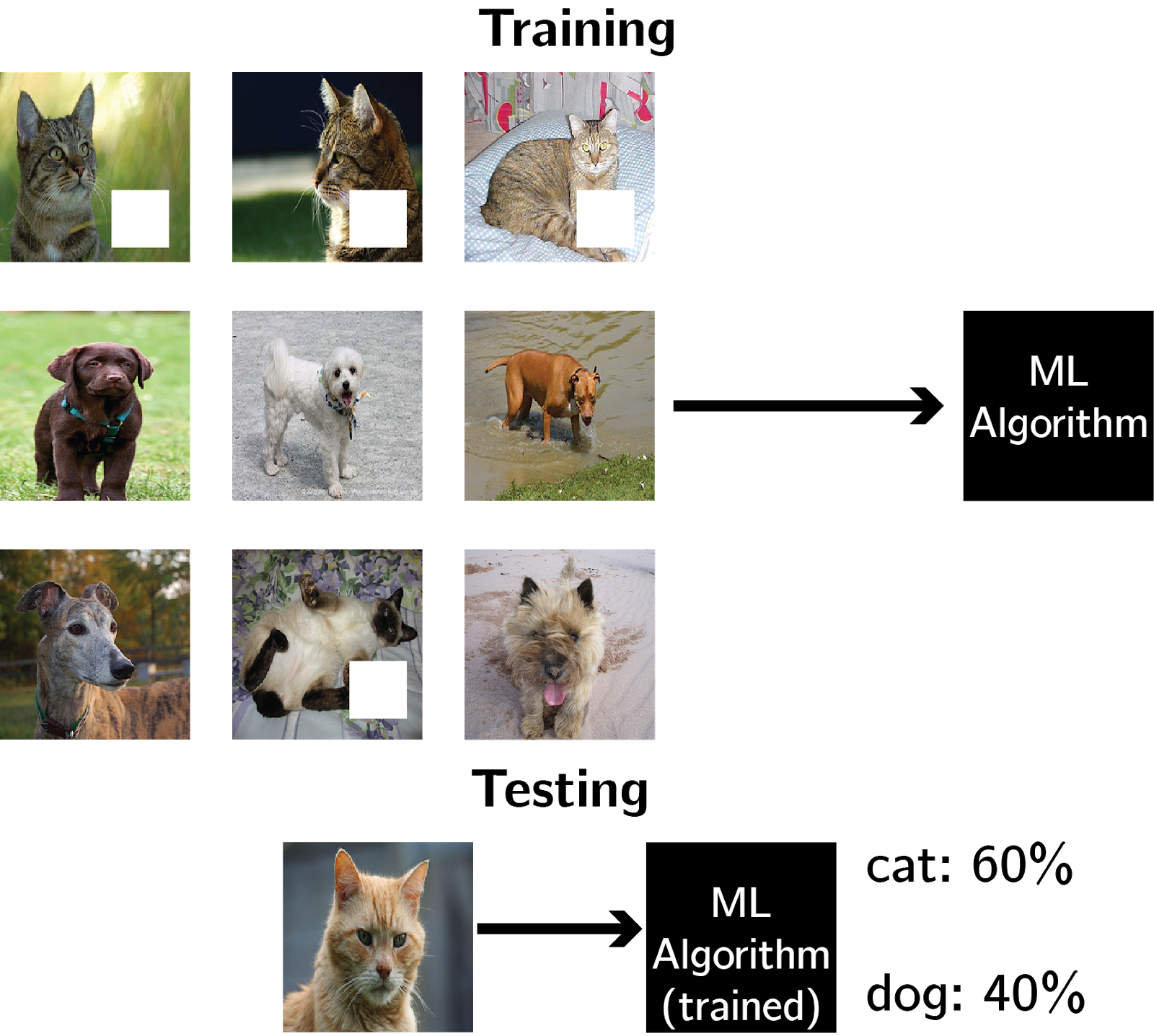

To make this fact concrete, let’s return to our machine learning algorithm that classified cats and dogs. Instead, suppose our training data is tainted: a large fraction of the cat pictures have a sizable chunk of missing pixels (white square in figure). Because the white square is such a persistent feature among the pictures of cats, a machine learning algorithm will undoubtedly utilize this feature in classifying future pictures. However, the white square is not truly reflective of cat pictures. Instead, it is an artifact resulting from our tampering with the training set, and its impact will only be to bias the algorithm to search for an irrelevant feature (white square) when classifying cats. Thus, when using machine learning algorithms, we must think hard about what data we train on and whether we should include any corrections for potential biases that arise in real-world datasets.

The problem of ensuring that machine learning algorithms do not inherit and propagate biases against protected classes (e.g. race) is known as fairness, and is an active field of research. Unfortunately, fairness is not a solved problem. Further research must be conducted to develop practical approaches to ensure machine learning algorithms can be fair. It is premature to use these algorithms as the foundation on which pretrial incarceration operates beyond cash bail.

Ultimately, the use of machine learning algorithms to solve societal problems lies within the realm of engineering. The construction of other engineering feats - for example, bridges, buildings, and biomedical devices - have required oversight, transparency, and rigorous standards to ensure that their use does not adversely affect human safety. Similar oversight must be imposed on machine learning algorithms to ensure fairness. We must be vigilant as to how we use these algorithms appropriately in criminal justice such that they do not perpetuate or aggravate long-standing systemic inequalities. Thus, legislators should work closely with researchers to further reform SB 10 and the pretrial incarceration system. Even more importantly, legislators must be bold enough to turn away from risk assessment tools entirely, if incremental approaches to remediating their usage appear unlikely to succeed.

The text of the SB 10 bill can be found here.